In Part 1 you got to relive with me my utter frustration at the way commercial travel in the US has devolved into a ritual of soul-death, inflicted on us by mammoth corporate overlords who have squeezed every last crumb of innocent pleasure out of experiences as pedestrian as boarding a 767.

It’s time for us to take it all back. It’s time to stop letting these multinational munchkins boss us around. And here’s how I did just that. Day 1 of 3.

Six hours after we convinced the Accountant of Doom at the front desk to let us in and have a nap, we were slamming down fajitas and texting the aircraft seller to arrange our pre-buy inspection and do all the transfer paperwork. In all honesty, the Mexican food is the only thing about Phoenix that I liked. Phoenix is an object lesson in how man makes ugly what he does not value. Land isn’t valuable on that godforsaken flatland so it gets used and abused and wasted in ways that dismay my inner resource economist.

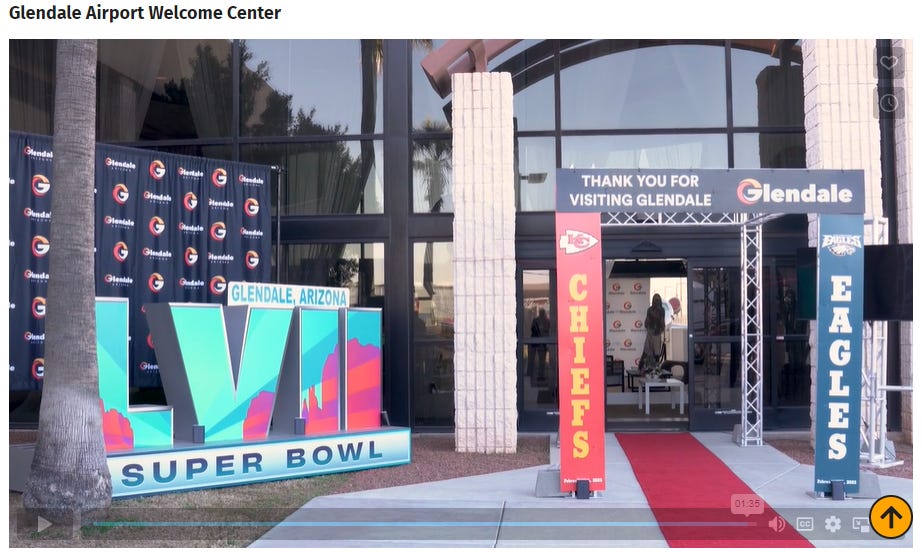

The plane was hangared at Glendale – a Class Delta that gets enough opulent bizjet traffic that the FBO can maintain a fleet of near-new crew cars, hand out cappuccinos and organic trail mix in the lobby, and provide both a flight planning room with up-to-date desktops and showers with herbal shampoo. They were massively proud of the fact that they had been the “Private Jet Airport of Superbowl LVII.”

Usually these jobs are kind of Motel 6. This one was shaping up as more of a Hampton Inn with an indoor pool and a hot breakfast bar. Both the airport and the plane were considerably more top shelf than Jack and I usually deal with. But this is the part of private flight where you actually have to exert yourself more than if you were flying commercial, or driving.

Any time a plane leaves the ground, it needs a meaningful preflight inspection. On a plane owned by a flight school or rental outfit a responsible preflight takes at least 20-30 minutes.1 You don’t trust the fuel gauges and you do more than kick the tires before you light the fires.

We had a more demanding task than that in front of us, as we had been contracted to inspect the aircraft on behalf of the buyer and confirm that it was in the condition that had been represented during the sales negotiations. This involves a combination of physical inspection of the airplane and a forensic look at the paperwork. It took the two of us about four hours to evaluate the plane and decide the deal was on and we would start the ferry flight the next morning. We buttoned the plane back up, topped off the fuel tank, loaded everything but the overnight bags in the luggage compartment, turned out the lights, locked the hangar, and went out for the Jack-in-the-Box we couldn’t find at 05:00.

But honestly, this plane barely needed an inspection. It was a factory-built Van’s RV-12 with less than 170 hours on the airframe/engine. It had been ordered as a flight school plane but in the delay between order and delivery the flight school had gone out of business; one of the former owners had accepted delivery and flew it as his personal plane until he decided he needed to move on to something bigger. The plane was an absolute creampuff.

(For those of my audience who are *not* aviation geeks but would like to know more about how an upstart in Oregon who started out making kits for experimental amateur builders to assemble can make better light trainer planes than Cessna, Piper, Diamond, or Cirrus can for a third of the price, here’s some background.)

So in comparing the fly-your-own-way experience to yesterday’s Southwest Hell, how are we doing so far? The next step will be entering the plane in preparation for departure. To get to that point at BWI we had to: drive an hour to arrive at the airport two hours early, leave our car in a parking garage, take a shuttle bus to the terminal, haul our bags through the airport, fuss with a kiosk to get our boarding passes, submit to TSA shoe stripping/electronic scanning, run for the gate, and sit on the plane for an hour before it moved. Four hours of unpleasant annoyance with nary a moment of self-actuated control over our situation save choosing the parking spot in the garage. Compare that to our Glendale experience, where we parked our rental car right outside the walk gate, walked 30 yards to the hangar, spent four hours assuring ourselves by application of our knowledge and skill that the aircraft was safe and legal to fly, and prepared it for departure.

The time element is just about a wash. But think about the difference in what these two approaches say about our ability to wield responsibility and control.

On Thursday night we were at the mercy of dozens of people whose faces we could not see and whose qualifications we could not examine, complying with rules and policies established and enforced by hundreds or thousands of others. We didn’t vote for any of these people or decide to do business with them based on our assessment of their qualifications – we don’t know what those are, because these people are anonymous.

On Friday, every step of this process was open, transparent, and under our control. We examined with our own eyes, and evaluated with our own tools, the aircraft to which we would be entrusting our lives the next day. We know ourselves – our competencies as pilots and mechanics. We know the reputation of the aircraft builder; Jack has been to the factory more than once and talked to the owner, the production manager, and the test pilot. We met with, and evaluated, the trustworthiness of the seller.

After three years of being ordered about and hectored by small, incompetent “experts” who turned out to be wrong about everything they said, I believe people are sick unto death of Thursday night. Let’s make America Friday again.

Tune in for Part 3, “High Flight,” soon. In the meantime I’m also putting some thoughts together on what it means to be a teacher, as it’s that part of my flight life that made it take so long to write Part 2.

As an aside — if we had a culture that demanded that before you drove a car you spent five minutes doing a pre-drive inspection the number of roadside breakdowns disrupting traffic would decrease by about 75%. Since the consequences of running out of fuel or having muffler mount break in a car are usually inconvenient rather than life-threatening, and most of the cost is externalized to the other drivers who endure the resulting traffic backup, I hold few hopes in that regard.