This is a story about how America works. Not the dystopian version of America being pumped by the sorry likes of Tom Schaller, Paul Waldman, Paul Krugman, and the “ThReAtS tO OuR DeMoCrAcY” chorus. A story about a couple of ordinary people making an ordinary living and seeing the glory and promise of our country shining in the faces and driving the muscles and minds of the people we meet while we’re doing it.

Chapter 1: The Embuggerment

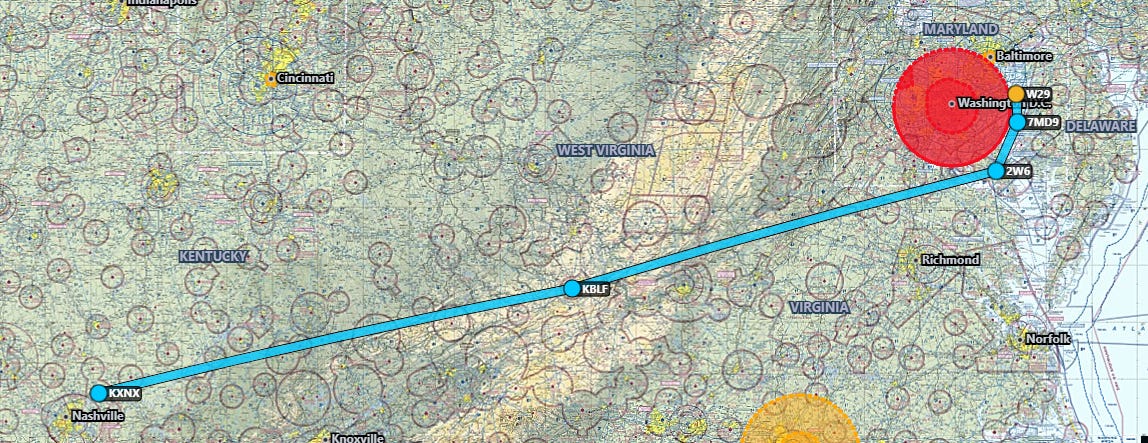

Jack1 and I started this job over a month ago, on February 16. We had been hired to ferry a small plane from its current home in Maryland to the buyer in Texas. We do these jobs often; we have the particular skills to pull them off and there are few competitors. It’s chancy work with a lot of variables and meager profit. Things often go wrong (as they did this time). There’s no reliable way to hedge the risk, which makes it an unattractive prospect for larger, stodgier, more ‘by-the-book’ companies.

The very existence of this particular make of airplane is a testament to small-scale entrepreneurial ingenuity. It was a 2007 Sting Sport — manufactured in the Czech Republic under expansive rules that opened up two-seat light sport aircraft designs outside the heavy hand of the FAA/EASA in the early oughts.

When we started out from Maryland at the ass-crack of dawn it was our intention to fly a couple of 3.5-ish-hour legs2 to Gallatin, TN, stay overnight, and continue on to the final destination of Denton, TX the next day in two legs.

Almost immediately, our calculations proved fanciful. Winds aloft were far more fierce than predicted and we were making 80 knots over the ground. All our careful pre-flight planning went out the window. That’s not at all unusual. We re-adjusted our expectations, identified better fuel stops, readjusted our path, and went on our way.

It was after the stop in Jasper TN — foolishly thinking we were in the home stretch — that we truly jumped the rails. Ten minutes out of KAPT the plane started making a noise later vividly described by people on the ground under our descent path as “a BMW motorcycle in death throes.” An exhaust pipe had cracked. In an automobile this would be an annoyance. In an aircraft — where the exhaust system is almost entirely contained within a cowl separated from the operators by a poorly sealed sheet of aluminum, and also serves as the cabin heat source via a primitive shroud — it’s a recipe for carbon monoxide poisoning. And in the case of a composite airframe, an inflight fire can ignite as the hot exhaust gases heat first the epoxy substrate and then the fiberglass/carbon fiber structure.

We had, we figured, at least 15 - 20 minutes to get on the ground before we were on fire. We had the choice of 180ing back to Jasper or proceeding to the closest airport with what looked like reasonable accommodations. That turned out to be Scottsboro AL.

We expedited our clattering aircraft onto the field and before we had it pulled to a stop on the ramp we had a couple of locals — one in a golf cart and another on a one-wheel — riding up to see what was going on and how they could help. They directed us to an open tiedown, loaned us tools, and stayed with us until we determined we couldn’t fix what had gone wrong with what we had at hand.

When we figured out that our best route back home was a flight out of Chattanooga the next day, the airport manager drove us there and dropped us at our hotel. During the downtime in between, our new friends showed us their own aviation playthings, entertained us with local color, and helped in a dozen little ways to smooth our rough landing. All of them just generally nice guys taking time to make a couple of strangers’ crummy day a little less crummy.

I was going to craft a pithy caption, but this airplane deserves a paragraph. This is a pre-war Waco Standard Cabin that used to be owned by Jeff Skiles. If you’re not an aviation geek — he was played by Aaron Eckhart in the movie. Miracle on the Hudson. Sully’s FO.

Yeah, we made an emergency landing at a random airfield in the middle of What’s the Matter with Alabama and got to rub elbows with the caretaker of a historic aircraft that used to belong to a hero celebrity pilot.

What a pity I’d left my Keith Olbermann spectacles on the nightstand at home. Otherwise I would have been alert to the White Rural Rage seething all around me. I would have framed this essay with a history of the Scottsboro Boys, claimed that the shop rags spilling out of the US General toolboxes were certainly recycled Klan robes, and had a word or two to say about the climate denialism wafting on the breeze scented with cosmoline and 100 low lead. Instead all I saw was geniality, generosity, good humor, interesting conversation, and a really nice antique airplane.

Having secured the crippled aircraft we got home the way virtually all normal people do — on Delta — and turned to obtaining the necessary repair parts and planning the return trip.

Chapter 2: Try Try Again

We had to wait for two pieces of replacement exhaust pipe to be shipped from the home office in Hradec Králové. That took a week — an amazing turnaround, given in other circumstances we’ve waited for months on parts from Italy or Austria. The return flight connected to Chattanooga through O’Hare — currently the second worst airport in the known universe. (The top spot has been permanently claimed by Atlanta Hartsfield.) But it wasn’t absolutely terrible. We arrived at CHA to early afternoon rain showers and a ride to Scottsboro with an old Georgia boy who was retired from a 30-year stint in a knife factory. He drives Uber to bring in some extra spending money and, based on the 90 minutes we spent with him, have someone to talk to who’s not his wife. He was a private pilot, or had been before cardiac problems cost him his FAA medical, so we had plenty to talk about.

The aircraft repair was equal parts relief and dumbfounded disbelief that for once something had gone more smoothly than planned. You know that feeling, right? Like…it shouldn’t have been that easy. Where’s that other shoe…waiting for it to drop. I’m not that gullible.

But actually, it was that easy. Jack did a return-to-service flight, everything was fine, and we made plans to leave as early as possible the next day.

The shoe dropped.

Earlier in the week, when we were pre-planning this flight, weather forecasts indicated the possibility of some cloud cover in the morning. We woke at around 06:30 local to a fog bank extending from Texas to New Hampshire. Somehow across the entire country east of the Rockies, the dewpoint and air temperature were exactly the same and neither one was changing. For hours.

So we dawdled as long as we could at the hotel and then limped the borrowed crew car back to the airport where we would at least have some fellow pilots with whom we could commiserate. We picked their brains for advice about avoiding terrain and obstacles on a westbound departure. We got to meet another White Rural Rager, in his 80s, and talk to him about his chosen instrument of colonialist oppression (an Aeronca Champ).

And then it was time to piss or get off the pot.

The ceilings lifted to marginal VFR on the airfield. We had been advised, and agreed, that it was safe to fly down the lake to the southwest where we wouldn’t encounter high terrain, or obstacles like transmission lines or cell towers. Weather reports indicated that once we had flown that far we would find higher ceilings and better visibility.

It actually worked for a while. We got to the foot of the lake and were able to climb over terrain and get an altitude we felt comfortable with.

And then it closed in again.

Tune in for Chapter 2 to find out how we made it back home (we did) and what other delightful Americans we met along the way.

The pseudonym of my particular gentleman friend, business partner, and unindicted co-conspirator in this, the last third of my life. He hasn’t given his permission to be publicly flogged on Substack, so Jack he remains.

In some ways flying a small plane cross country is like driving a car cross country in 1915 would have been. You have to stop for fuel, but you have to calculate beforehand how far you can fly on a tank of fuel and check to make sure there will be fuel somewhere near there. That information is available in the 21st C. digital version of The Green Book. The length of your legs is determined by two kinds of endurance: fuel endurance = ((groundspeed x fuel capacity)/(gallons/hr)) - (0.5*groundspeed) [to account for an FAA regulation that VFR flight must conclude with no less than 30 minutes of usable fuel on board]; pilots’ butt endurance = not such a precisely defined equation but is a function of both age and liquids intake.

Cool account. :)

Can't wait for more adventure!