I’ve received a lot of positive feedback on my aviation posts. Thanks to everyone who appreciates that content, and there will be more of it, soon. Also, I’m getting caught up in the Matt Taibbi/Michael Schellenberger/Eugippius/El Gato Malo vortex.

But later. Right now I’m switching gears, because a new season is upon me. Renaissance Faire season.

Cue the jokes. Believe me, I know the tropes and recognize they’re rooted in reality. Put a socially awkward high-functioning autistic in a Viking tunic and give him a pikestaff. Or stuff a middle-aged wine aunt with a 32 BMI into a leather bodice and a plaid miniskirt, give her a 40 oz drinking horn, and set her loose.

Not that there’s anything wrong with that, but my faire’s not like that. At least it’s not only like that.

The Virginia Renaissance Faire is run by a 501c3 educational non-profit. We have plenty of goofy fun, and we serve plenty of booze, but we also take seriously our commitment to provide learning along with the entertainment. I’ve been appearing at this faire since 2008: I do a stage act playing traditional Celtic harp music; I play whistle and recorder in a minstrel troupe that provides music for dancing; and I portray a lower-class itinerant Irish peasant hiding in an English shire from her husband’s family, which provides an opening to talk about how Irish marriage and property law were both different from English custom and more or less unique in that time and place. In my adorable Lucky Charms accent.

This is an extension of my love of teaching. Music can be a gateway into people’s souls, if you will just wield the opening responsibly. I am by no means an accomplished harper. I practice haphazardly and rely on easy, cheap tricks of tempo and dynamics to give the impression I have far more skill than I do. But I’ve found it hardly matters. The harp generates an aura of beauty almost independent of the abilities of the harper. You can set a harp crosswise to the wind and it will make music all on its own.1 You can invite a five-year-old to the stage and let her run her hands up and down the strings, and the effect is no less magical than a glissando performed by a Salzedo-trained professional. They sit down to listen to the music, and get roped into history. My histories. Mes histoires. Because, orthogonal to the “herstories” nonsense, the root of history isn’t “his.” It’s “story.”

And the stories are so juicy! Ossian, the Homer of the Scots. A third century bard-warrior; the last Chief of the Fenians. Or perhaps not…Samuel Johnson thought it was a load of horseshit when it was new, and the consensus today is that it was a hoax, albeit one that roped in many intelligent contemporaries.

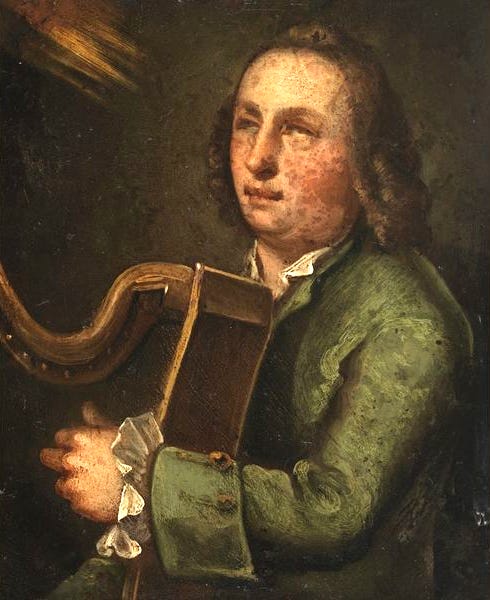

Turlough O’Carolan — the blind harper whose performances and compositions define the Golden Age of Irish harping. Over 200 of his tunes are known to us today, even though he never wrote them down. Harping was passed through from hand to ear back then, and few performers, even the sighted ones, could notate music. Carolan died in 1738, but his compositional legacy was passed on by those who had heard him perform, and passed on again, for generations. In 1795 The Powers That Be (Imperial British Edition) decided that even though they had spent a couple of centuries trying to eradicate traditional harping in Ireland — because in the language of today it was stochastic terrorism — they would now support it being preserved in embalming fluid. The Golden Age harpers were all now dead and anyone who had ever learned directly from them were in their 80s.

A festival was organized in Belfast, and the English-educated Edward Bunting of Armagh, a 19-year-old classically trained organist, was engaged to listen to the ten performers and transcribe what they played. General Collection of the Ancient Irish Music was the result. But Bunting had been infected with a love for this music and spent the rest of his life revisiting the ten original harpers and their apprentices and casting his net among their peers — hunting, collecting, and transcribing as much as he could find. By 1840 he had located and published pianoforte transcriptions for 214 Carolan tunes — these form the basis for what we know today about this rich vein of music.

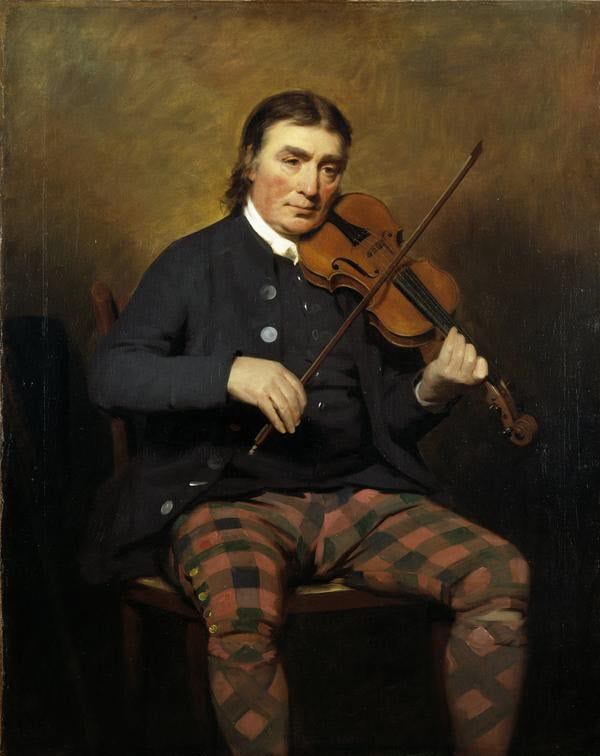

Niel Gow — a fiddler whose life spanned most of the 18th century.

Father to four fiddler sons, whose most famous composition is a heartbreaking lament that honors the death of his second wife in 1805. According to legend, when she died he set his fiddle on a shelf and did not touch it for months. When he finally took the instrument down, he set it under his chin and that is what poured forth.

Every time I play it, I try to imagine what he felt.

He followed her into the hereafter two years later. (The telling of that story, and playing that tune, always highlights the happily settled couples in the audience — they are not looking at me, but at each other.) The 20th C. English composer David Gow was his direct descendant. The Essential Niel Gow remains to this day a foundational resource for any performer who aspires to competency as a traditional Scottish fiddler.

So for the next six weeks that’s where my head is situated. I’m going to put on funny clothes and play music in the woods. I’m going to watch people dance, and drink, and buy handcrafted goods, and I’m going to entertain them in the background. I’m going to talk to them about Turloch O’Carolan, and Irish independence, and how cultures survive under threat. I’ll sing to them in Irish.

And as long as people are doing things like this, the arguments about AI extinguishing organic life, or the panics about governments abolishing our free speech, or….whatever doomberg thing you’re listening to…just doesn’t matter. I’m going to play music for drunk people wearing funny clothes in the woods. We’re going to be human. If you try to take that away from us, you will find yourself facing a Viking horde.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Aeolian_harp