And so off we launched the next morning. We didn’t quite make it out at the crack of dawn but we weren’t far off. A quick once-over, rechecking we’d packed everything we meant to and nothing we hadn’t. Rechecking the fuel level and testing for water contamination (even though we’d done that right before leaving the plane yesterday and it had been locked in a hangar ever since). Fire up the engine, check the oil pressure. Listen to ATIS to get the winds and barometer. Program the first leg on the GPS. Call ground control.

Glendale is a Class Delta, meaning there is a control tower but seldom any radar coverage on the field. The controllers maintain separation by looking out the window through binoculars. They may, and increasingly do, get a feed from a remote radar location which they use to increase their situational awareness of what their traffic looks like, but they are primarily concerned with visually spotting planes approaching and keeping them separated from each other and from the planes moving around on the airport seeking to depart.

“Glendale Ground, 3-4-5-Foxtrot-Charlie”

“5-Fox-Charlie. Go ahead”

“5-Fox-Charlie is at the north T hangars ready to taxi for northeast departure with information India.”

“5-Fox-Charlie taxi via Alpha hold short runway zero one”

“Taxi Alpha hold short runway Zero One 5-Fox-Charlie.”

It’s a kind of radio shorthand, all spelled out the Pilot-Controller Glossary section of the Aeronautical Information Manual. I’m still a complete goober at talking to ATC; I did all my training and 95% of my subsequent flying in the aviation boondocks where your radio communication is listening to bored morons meowing on Guard and self-announcing your position on the common traffic airport frequency. So Jack did that part.

Getting out of Glendale was a bit of a dance. It’s nestled under the outer shelf of the Phoenix Sky Harbor Bravo and right next to Luke AFB, so you have to be careful about staying at the right altitude so you’re not busting restricted airspace.

And that’s why the transmission from Glendale tower after we’d climbed to about 800 feet AGL was not at all welcome:

“5-Fox-Charlie: Transponder altitude not observed.”

Goddamn it. This is going to be a problem. But later.

Flying in the western half of the US is mostly managing altitude. Climb to whatever height is required to avoid all the pointy stuff and stay there until you hit Missouri. You are required to have supplemental oxygen for the pilot if that number is 12.5K feet and you stay up there for more than 30 minutes. Don’t question why 12.5K feet is the magic number. The FAA says so. (Here’s a personal admission: I start feeling altitude at around 9K. If I spend more than four hours that high I can feel it for 24 hours. If I spend more than four hours at 11.5K without oxygen – as we did for most of this day -- I am retarded for 48 hours. That gets filed under “Personal Minimums.”)

We picked 11.5K for the first part of the trip because that provided us ample clearance over the terrain and enough gliding distance to make it to the least unattractive landing spot in case of engine failure. There are no great off-airport landing spots in much of that country, and the airports, even little private strips, are few and far between. The best-glide-speed ratio of a factory RV-12 is about 12 to 1. Meaning for every 1000 feet of altitude you can glide engine out 12,000 feet (a little less than 2 nautical miles) horizontally. That’s a little optimistic, and of course you have to factor in headwinds, but it’s safe to say from a height of 11.5K you could glide at least 20 miles.

Oh, another thing I should explain. If you are flying VFR, you are supposed to fly an altitude that corresponds to “East is Odd but West is Even Odder.” That is, if you are flying a magnetic heading from 0 to 179 degrees, you fly at odd altitudes plus 500 feet: 5500, 7500, 9500, 11500, etc. If you are flying 180-359 degrees, you fly 4500, 6500, 8500, 10500 etc. This is to deconflict traffic headed in opposite directions and to keep you out of the way of instrument flights, which are flying on the thousands (4000, 5000, 6000, etc). So since we were flying east we picked 11,500.

A big part of private pilot training is learning to always be finding the field you’d glide to if your engine quit right now. That’s easy where I trained, on the Maryland Eastern Shore. The entire peninsula is a plausible off-airport landing site of farm fields and two lane roads, and it’s all sea level. Even if you have to ditch in the Bay you’re within sight of a couple dozen fishing boats or cabin cruisers who will either come to your aid or call you in on the marine emergency frequency.

But when you’re sailing a couple thousand feet AGL over very pointy rocks, all that goes out the window. Yes, there is usually a path downhill to a valley a few thousand feet lower than your current position. You look for them on your sectional chart or GPS equivalent and hope to hell you don’t have to find out if you can make it without engine power.

This is one of the things that separates pilots from drivers. If your car craps out on the highway you might, under certain circumstances, be shamed by your predicament. If you blow a cylinder or drop an oil pan in the middle of the Chesapeake Bay Bridge you will end up on the local news and your car will get videoed by the Queen Anne County police helicopter and it will be very embarrassing. But you won’t die. Your body won’t lie undiscovered until the Civil Air Patrol finally widens its search grid to include the 100 nautical miles after you strayed off your filed flight plan…did you file a flight plan? OK, they might still be looking.

But I started out to tell you how flying this plane from Phoenix to Baltimore was liberating, not terrifying.

Here’s the crux: your liberation comes with a side order of terror. To take charge of your sky self is the ultimate act of fuckitol. You are the pilot in command. That means you, and only you, are responsible for the safe conclusion of the flight. This is a frame of mind, and a set of skills, that carries over into everyday life in ways I haven’t even begun to completely catalog.

But once you begin to do it in the sky, you start to do it everywhere.

One aspect of flight planning in small planes is figuring out where to get fuel. It’s not like the interstate, with a Pilot, a Flying J, and a Buc-ee’s at every big interchange. The plane we were flying had a fuel burn of 4 gal/hr and a 19 gal. tank. Under day VFR you are required to plan for a destination that leaves at least 30 minutes of fuel (so, 2 gal) in reserve. So we could at a maximum fly as far as 17 gal of fuel would take us.

And here’s another way that flying is different from driving. Your car is rated in miles per gallon. Planes are rated in gallons per hour. And how far you can get in an hour depends on your ground speed, which is a combination of your plane’s cruise speed and the prevailing winds.

It just so happened on this flight that we had *blistering* tailwinds. Indicated cruise airspeed in this plane is 108 knots. Because there was a massive wind from the west we were seeing ground speeds at times of 150-160 knots. It’s a gift from the gods. (On the other hand I’ve done this flight the opposite way, east to west, in a 65-hp Luscombe built in 1939, with a published cruise speed of 95-100 mph. I believe in Idaho the speed limit is 80. I watched an entire parade of semi-trailer trucks outpace me as I fought the headwinds. I’ve seen small planes hover in place as the headwinds exactly matched their forward thrust.)

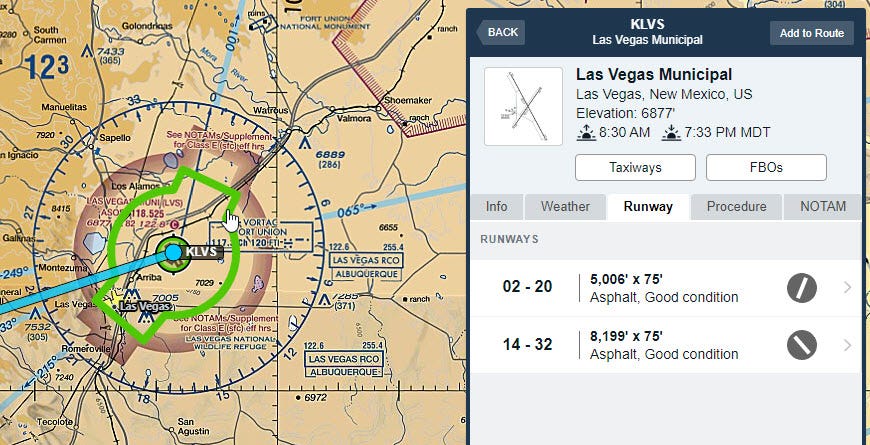

So we planned our first stop at Las Vegas, NM.

In addition to being about the right distance, it had another attractive feature – intersecting runways, both way longer than we needed to land the plane. Blistering tailwinds at altitude don’t go away at the surface. To bring this plane to the ground we needed less than 15 knots of crosswind. Your odds of finding that are greatly increased when you have four choices of landing direction.

Las Vegas was frustrating, because it was an airport that should have had a marketing advantage and it just didn’t live up to its potential. The self-serve fuel farm was poorly equipped and the FBO wasn’t manned. After trying three different credit cards we finally got it to work, but…c’mon. I would have given you a four star Yelp review if you had at least restocked the snack machine with Lance crackers or had hand wipes in the bathroom. Which smelled like the gates of Hell, but I understand you can’t control that sulfur dioxide in the groundwater thing. Still.

I can’t believe I have to split the first day into multiple posts, but this is getting too long. We will continue on, and eventually end up at a delightful airport in Missouri, in the next installment.